Back to the Future of Wine

The Richard Sommer Story Part 1

On April 29, 1970, The News-Review published a relatively new wine column called the Vintage Edition. The topic? Oregon’s first annual wine festival, and the man who graced the front page of the feature was none other than the Father of Oregon Wine, Richard Sommer.

Now, coincidentally, 55 years later, I find myself writing for The News-Review about the same man.

The Umpqua Valley is known as the birthplace of Pinot Noir in Oregon, but many people might not know the story of how it all started and who started it.

That man is Richard Sommer, the catalyst who ignited the Oregon wine scene and founded HillCrest Vineyard, the first estate winery in Oregon since Prohibition, just 20 minutes from Roseburg.

The wine world has many colorful characters, and Sommer was no exception. Encounters with Sommer were anything but predictable. More than once, visitors walking along the gravel path to his tasting room were startled by a shirtless man jumping up from the vineyard, only to find out it was the owner himself.

So, who was Sommer? A farmer, scientist, and what sounds like the wine equivalent of Doc Brown in “Back to the Future.”

Often seen wearing overalls, round spectacles and carrying a pencil in one pocket, Sommer filled notebook after notebook (and subsequently box upon box) with notes, documenting every thought that crossed his complex mind. Some say that brilliance was the half-sibling of madness, and for Sommer, the scientific streak was likely hereditary; his father was California’s first marine biologist and the first scientist to study Red Tide, the poisonous bacteria in shellfish.

Sommer was a California native and a veteran of the Korean War. After concluding his studies at the University of California, Davis, he migrated to Oregon armed with a degree in agronomy and vine cuttings from Louis Martini’s Carneros vineyard.

“Martini's vineyard was the site of the first Napa Winery," said Dyson DeMara, the now owner and winemaker at HillCrest Vineyard. “The winery was named Talcoa, which was originally started by the father of the Missouri wine industry, George Hussman.”

With cuttings ready for planting, Sommer began surveying land from the Applegate Valley, near Medford, to the Willamette Valley in hopes of starting a winery.

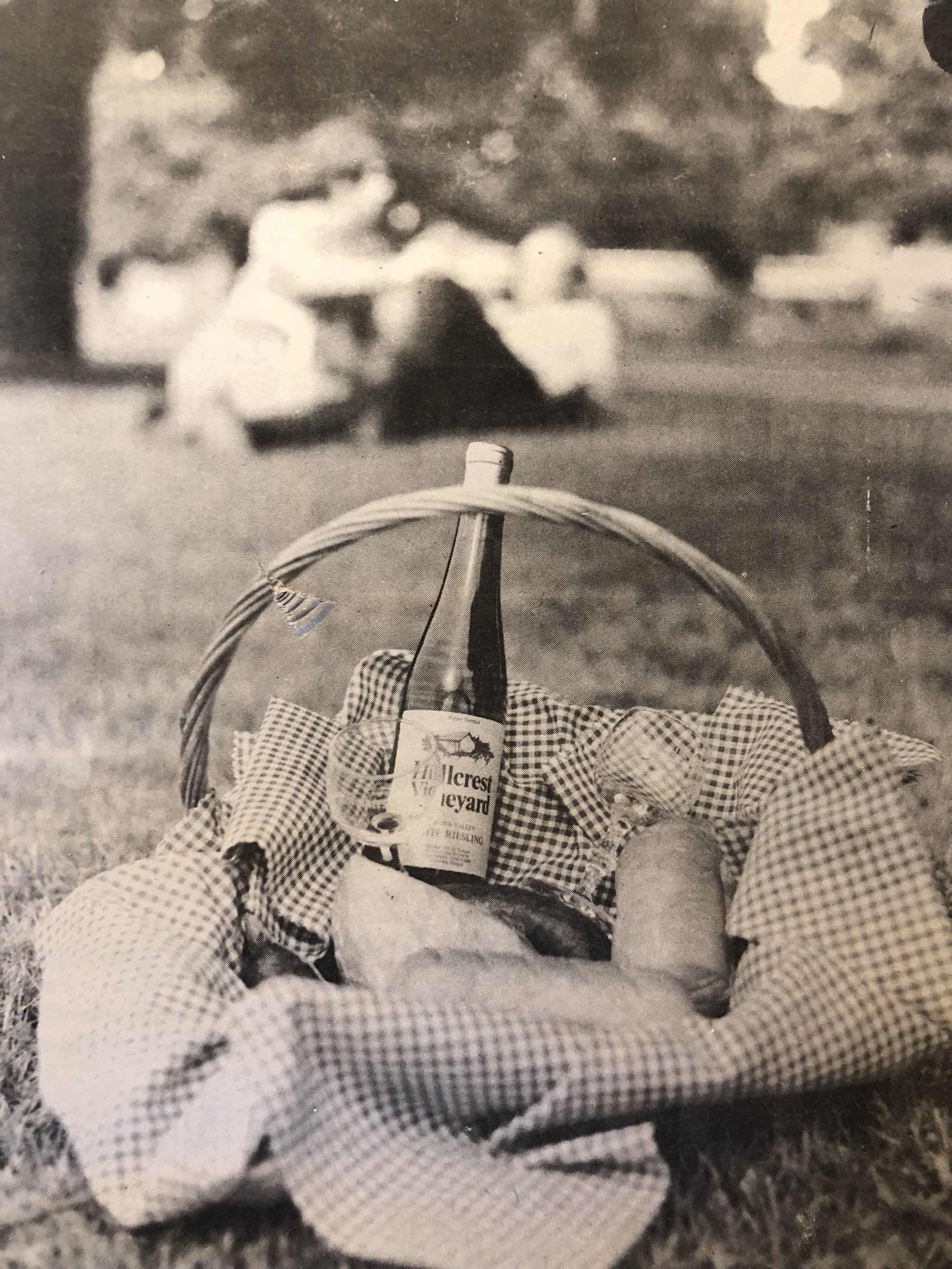

Advertisement of Sommer’s Riesling, 1970

Colleagues and professionals from UC Davis warned Sommer that Oregon was simply too cold and wet to grow grapes. But after meeting the Doerner brothers in the Umpqua Valley, a German immigrant family who had produced Zinfandel in Melrose since the late 1890s (and distilled brandy until their distillery closed in the 1960s), those myths were quickly shattered.

Using the Umpqua Valley as his base of operations, Sommer took a job at the Douglas County assessor's office and lived modestly in a tent near the Steamboat Inn. During this time, he purchased fruit from old pre-Prohibition vineyards across the Willamette, Rogue and Umpqua Valleys, fermenting them separately and evaluating each region. He found the Umpqua Valley fruit to be his favorite.

“(Sommer) was here to make wine that competed with the famous European wine regions,” said DeMara. “He wanted to be a pioneer and had a natural draw to innovate. With his Swiss upbringing, wine was simply a daily accompaniment to meals. They made wine to share with family and friends around the table."

Richard Sommer pruning vines during winter at Hillcrest Vineyard

Still searching for a proper vineyard site, Richard received word from the Doerner brothers about a neighboring retired turkey farm in the Umpqua Valley. Purchasing the 20-acre plot in the Melrose area of Roseburg, Richard transplanted vine material he had been nurturing on his uncle’s Valley View Vineyard and Orchard in the Applegate Valley.

Richard in the 1970’s with his elaborate trellis system

Sommer’s newly established vineyard property in the Umpqua Valley soon became a living experiment. Different trellising systems could be seen dotting the landscape, some with 10 to 20 wires. According to DeMara, Sommer called the vines his “babies,” and his vineyard occasionally looked more like a Rube Goldberg machine than a manicured wine estate.

Historically speaking, Sommer is most widely recognized for introducing the first Pinot Noir vines to Oregon –the state’s most widely planted grape. Sommer’s first Pinot Noir bottling – his inaugural 1967 vintage – will forever grace the history books of Oregon wine, launching an unprecedented movement in the state’s wine history. Few realize, however, that he was also the first to bottle Malbec and Barbera, and the first post-prohibition Riesling, (not to mention a dozen of other grape varieties). In total, his estate housed over 35 grape varieties. For context, most wineries today grow 5 to 10 varieties, but 35 was fitting for Sommers’ experimental mindset.

An old photograph of Hillcrest Winery during the early days after Richard had constructed his vineyard

In Sommer’s April 29, 1970, article in The News-Review, he outlined what drew him to Roseburg to grow wine grapes: “Roseburg is blessed with a climate remarkably similar to the great wine growing regions of France,” he said. “We have the potential of making some of the finest wines in the world that cannot be matched or duplicated, and the key to this is our unique climate.”

Surprisingly, Sommer had no formal winemaking experience. He learned entirely from observation and the scientific curiosity that results in surprising innovation. Sommer purchased dairy tanks from Los Angeles, shipped them to Oregon, and repurposed them for winemaking, long before stainless steel became industry standard. At the time, only Château Latour winery in Bordeaux had begun experimenting with stainless steel tanks; most wineries still used leaky, unsanitary wooden tanks.

Newcomers to the wine industry sought Sommer’s help in those early days. Philippe Girardet of Girardet Vineyards was one such individual, working under Sommer before starting his own winery. A black-and-white photo immortalizes that history: Girardet, soaked to the bone during harvest, standing in Sommer’s HillCrest Vineyard.

The 70s were a time of significant growth for HillCrest Vineyard and Sommer’s wines, which eventually lined grocery store shelves, proving there was a promising future. His wines were gaining traction, particularly his Rieslings (the most expensive wine varietal in the world at the time). It wasn’t until one fateful evening, however, that it became clear that HillCrest Vineyard wasn’t just making wine for family and friends, but wines unlike anywhere else in the world.

TO BE CONTINUED NEXT WEEK…

This article was originally posted in the News-Review.